As promised, dear friends, here is a short overview over the history of that magical island that my darling Ian and me visited on our summer holidays last month – Ellan Vannin, aka the Isle of Man.

As I’ve said before, the island has had a particular significance due to its strategic position right in the middle of the Irish sea, with almost equal distance to Scotland, England, Wales and Ireland. Its culture has had many influences from different peoples, which has made it an absolutely unique place. But let’s start from the beginning…

The first settlers, Mesolithic hunter-gatherers, came to the island around 6,500 BCE; in those days, there were abundant food sources for the people: forests for hunting and gathering fruit and roots, rivers and coastlines full of fish and seafood. They lived in pit houses in small groups and knew how to make small tools for catching their prey.

Around 4,000 BCE, a new era started when a neolithic people brought farming and pottery: a unique culture called the Ronaldsway culture developed, and the population started to grow. Megalithic monuments and tombs were built, like the stone circle known as Ballahara Stones and ‘King Orry’s Grave’ in Laxey – which, dating from around 3,000 BCE, of course doesn’t belong to the medieval king we’re going to come across later…

Around 1,800 BCE, the Beaker people from Central Europe reached the island and brought with them the first metal: bronze. They were able to make better tools now for hunting and agriculture, and the population grew more quickly, which led to deforestation due to the high demand in wood for building houses. The groups became larger and more organised and specialised and started trading with people in Ireland and Cornwall, and artisans made beautiful pieces of jewellery for the well-off ladies of the Bronze Age.

Then, around 700 BCE, the first Celts came in from Britain (they spoke Brythonic, which is related to Welsh), and about 200 years later Goidelic Celts from Ireland arrived; their Gaelic language finally prevailed and formed one of the foundations of today’s Manx language. Like elsewhere, the Celts build roundhouses and hill forts and were organised in tribes with a chieftain, a warrior elite and a druid, and they brought their gods with them, one of whom took on a special rule for the island: Mannanan mac Lir, who gave Mannin, as the Celtic inhabitants call it, its name. (Or so they say; another theory is that ‘Ellan Vannin’ – Mannin mutates to Vannin as it does in Celtic languages – means ‘mountain island’, just like the Welsh island further south known as ‘Ynys Môn – Anglesey…)

Mannanan is said to have resided on the hill fort South Barrule, which still exists in remarkably good condition.

Just like in Ireland, the Celtic culture on Mannin continued undisturbed through the Roman era because the Romans, even though they knew of its existence, never set foot on the island. Also, largely from Ireland, Christianisation began in St. Patrick’s days (5th century), the first wooden churches were built and large numbers of distinctive Celtic crosses erected.

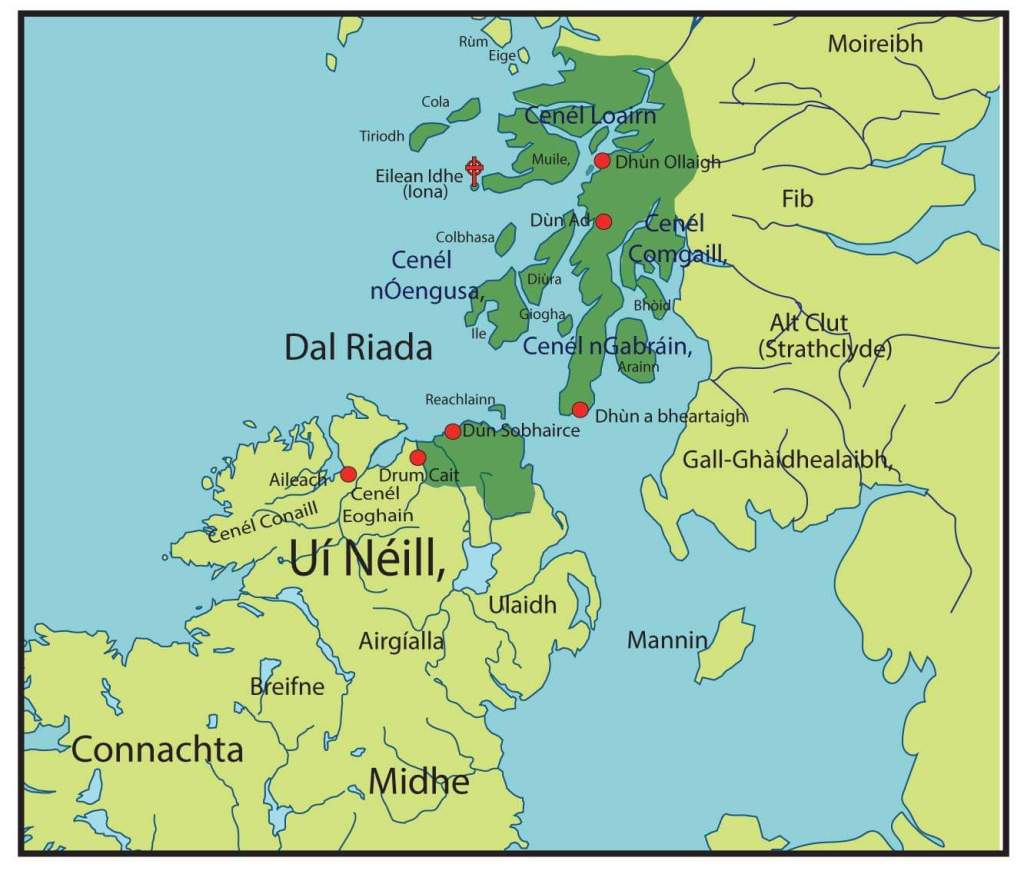

In those days, Mannin was ruled by the kings of Alt Clut, or Strathclyde, which, even though today part of Scotland, was then a Brythonic kingdom and part of the Welsh-speaking Hen Ogledd; king Tutwal (around 485) is the first one known by name. Around 100 years later, though, Baetan mac Cairill, king of Ulster, annexed Mannin and it became part of the mighty realm of Dal Riata.

Mannin kept being a coveted prize for would-be conquerors from all over the region: the Welsh, the Britons from Hen Ogledd and the Angles who were rapidly conquering the old Celtic Britain all had an eye on the island – and then, around 800, a new force came on the scene with a big bang: the Vikings.

Like in England and Scotland, they started out raiding and plundering, but after a while they actually settled on Mannin, and began to merge with the Celtic population into that unique mixture called the Norse-Gaels.

Like in Ireland, the native Celts had built massive Round Towers for their defence and protection from the Vikings, like the one on St. Patrick’s Isle right next to the church; but once the Vikings under Ragnall ua Imair (from the Dublin branch, installed there since 841) had conquered Mannin from the Welsh rulers in 902, together they built bigger defence buildings against Danes, Norwegians, Irish and Anglo-Saxons.

The Vikings became christianised by the Celts and largely became integrated into their society, but they brought with them their language, parts of which seeped into Manx, their enormous knowledge of shipbuilding, and also their democratic decision-making system: from 979 on, on Tynwald Hill, a parliament got together every Midsummer Day to decide on court decisions and new laws – the oldest continuously functioning parliament in the world!

Still, the threats were manifold, and Mannin changed hands numerous times in the Middle Ages: some of their most famous rulers were Olaf Sigtryggson (941-980), Sigurd the Stout of Orkney (990-1005), Haakon Eriksson of Norway (1014-30). Murchad mac Diarmata of Leinster (1061-70), and of course Gofraid Croban (or Godred Crovan in Norse, 1079-95), who usurped the throne, fought the Anglo-Saxons and set up a new legal system, and who is probably identical with the legendary King Orry to whom the neolithic grave in Laxey is attributed…

After Gofraid’s death, a civil war broke out on Mannin between the old Norse-Gaelic clans and the supporters of Jarl Ottar who had been put in charge by Magnus Barelegs of Norway; the Battle of Santwat in 1098 is the bloodiest chapter in Manx history and decimated the population of the island drastically. It also resulted in the subjugation of Mann by Norway and continuous fights between the conquerors and the descendants of Gofraid – until one of the most illustrious figures of the time came along: Somerled (Somairle in Gaelic), Lord of the Isles.

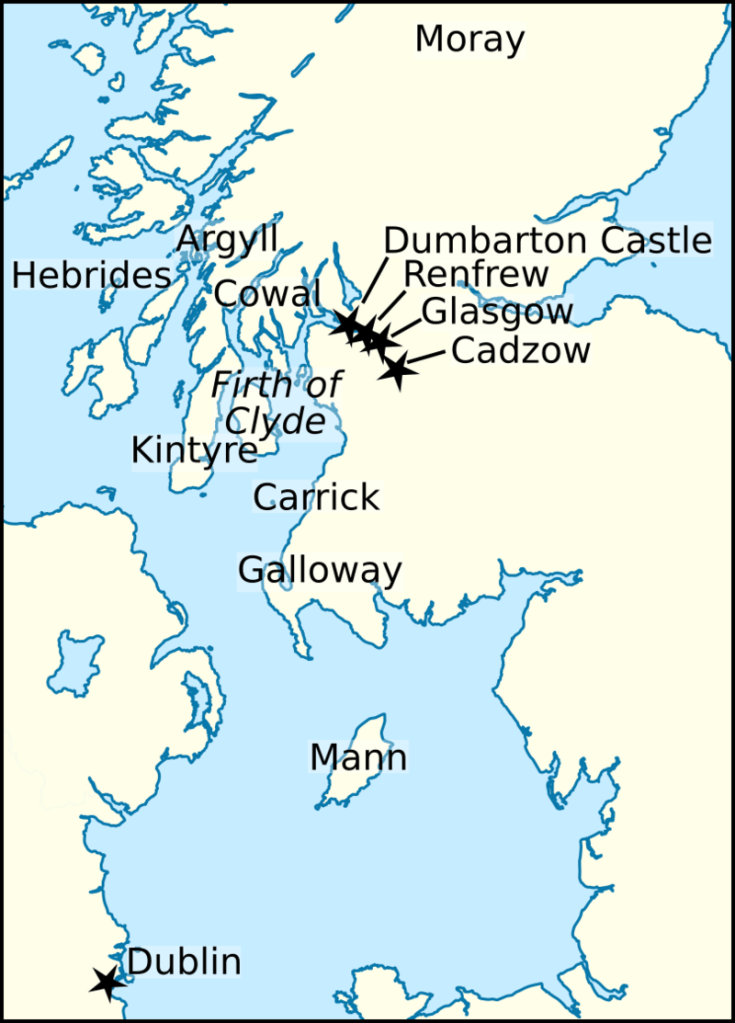

Born in Ireland to a Norse-Gaelic family, Somerled became Lord of Argyll and Kintyre, and then married Ragnhild, a great-granddaughter of Gofraid, and by defeating his brother-in-law Godred the Black restored what had once been the Gaelic kingdom of Dal Riata. He is revered as a Celtic hero (even though he himself, of course, was of mixed ancestry) in Mannin, Ireland and Scotland, and he is the ancestor of the Kings of Mann and the Isles and of several Scottish clans. In 1164. though, while leading a major invasion force into Scotland, he was killed in the Battle of Renfrew.

Unfortunately, subsequent rulers of Mann became more and more friendly with the English, they started paying homage but at the same time they were also obliged to pay tribute to Norway; feuds within the royal family (Rognvaldr and Olafr, 1188-1229) didn’t help, either, and so Mann finally became a vassal of Haakon of Norway in 1237.

Soon, though, Mann again changed hands: after Haakon’s death, his son Magnus VI decided to gift the island to Alexander III of Scotland, who’d had an eye on the precious trophy for some time, with the Treaty of Perth in 1266. But fate then played into England’s hands: after Alexander’s death, his 7-year-old granddaughter Margaret, Maid of Norway, daughter of king Eric II, who had inherited the Isle of Man as a dowry, died in 1290 on the way from Norway to England where she was supposed to marry Edward I’s young son – and so, in his usual greedy way, Edward ‘Longshanks’ declared Mann his own!

A long fight with the Scottish followed, and Robert Bruce temporarily managed to recapture Mann, but in 1333 Edward III decided to instal William, Earl of Salisbury as King of Mann – a nominally independent kingdom until Henry IV reclaimed it in 1399 and installed his own choice of kings but remained their feudal overlord. So, in 1405, the long reign of the Stanley family began.

The Stanley family, Earls of Derby, brought some stability to Mannin, albeit with a good dose of suppression, and the ties to the English crown and court were undeniable; also, during the English Civil War, James ‘the Great Stanley’ harboured monarchists on the island, which didn’t go down well with Cromwell and he ended up being executed in 1651.

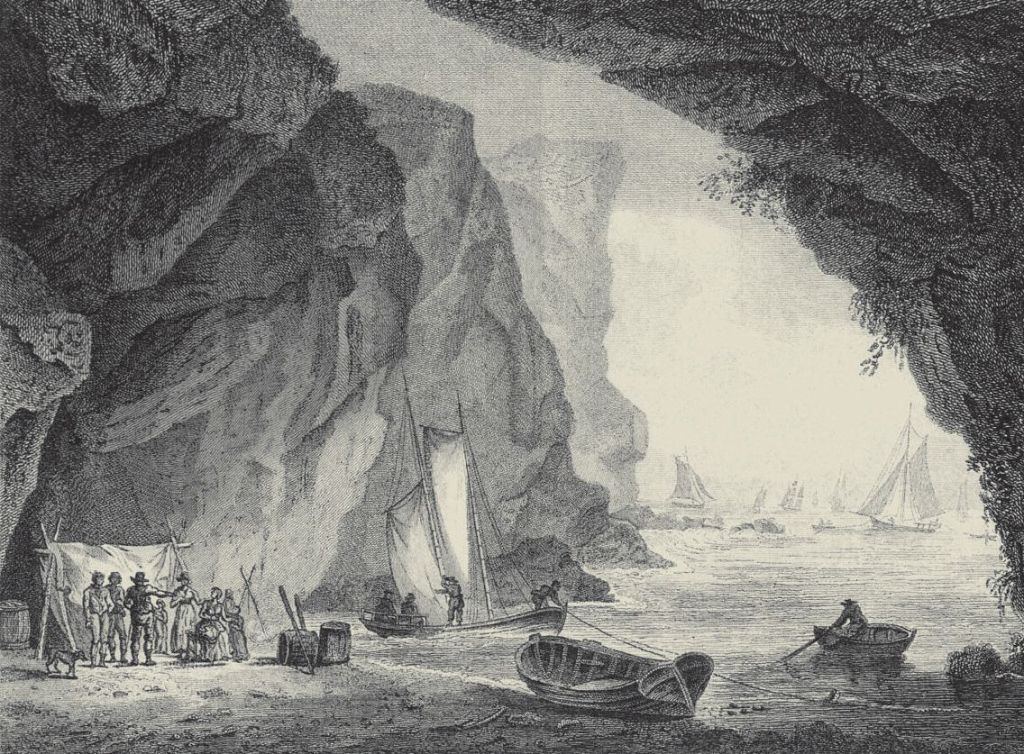

The Stanleys were restored to the throne of Mannin in 1660, but new rebellions soon broke out because of the burning leasehold question that had made it impossible for many farmers to retain their land; many of them were so dissatisfied and desperate that they gave up farming for good and went on to fishing – or the more lucrative pursuit of smuggling, which before long took on considerable dimensions on the island!

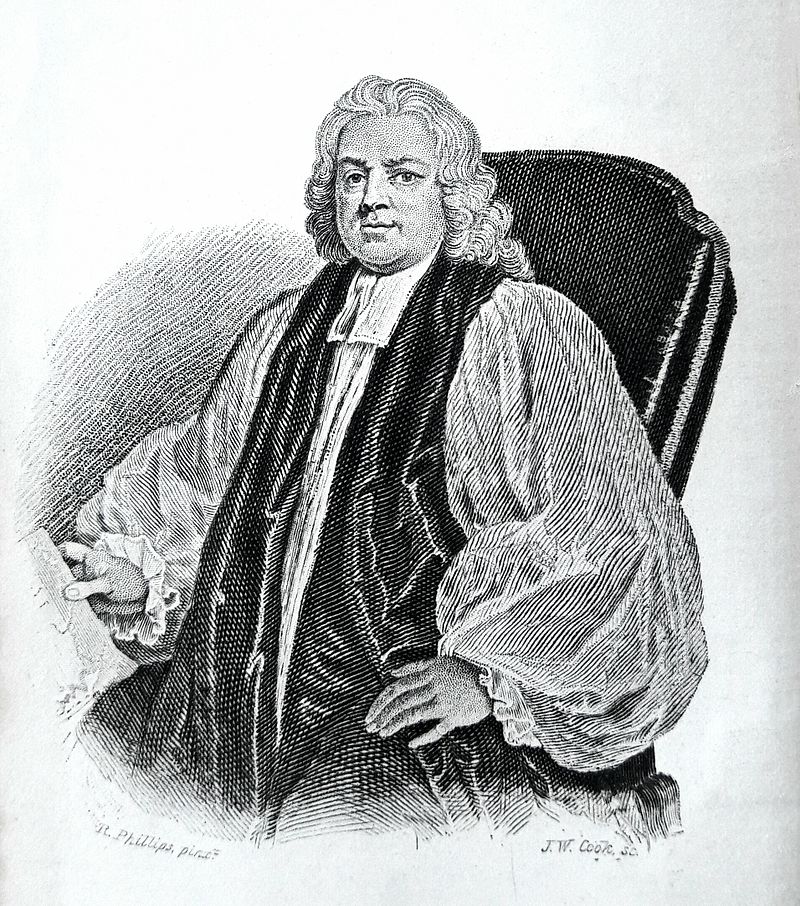

Bishop Thomas Wilson, beloved by the Manx people, finally managed to convince James Stanley in 1704 to an Act of Settlement which gave tenants security and a fixed rent to pay. When Wilson died aged 91 in 1755, nearly the whole population of Mannin attended his funeral.

In the 18th century, Mannin got better connected with the British mainland: a regular ferry service was set up, and more visitors started coming to the island. Meanwhile, after James Stanley’s death, Mannin fell to the Murray family of Atholl, and in 1765, Charlotte, Duchess of Atholl, sold it to the British Crown for £70,000 (Isle of Man Purchase Act), and Mannin became what it remains until this day: a Crown Dependency.

London started interfering pretty quickly with Mannin’s politics: a Smuggling Act was passed which imposed customs, duties and shipping regulations on the island. Also, the Manx language started suffering from not being allowed in schools or any other official institutions: according to an 1874 census, only 30% of the population actually still spoke Manx at home, and by 1901 the percentage had gone down to 8%!

Tourists, though, started coming to the island in large numbers, especially from neighbouring England, when the Isle of Man Steam Packet Company set up a regular service in 1830 that was much faster and safer than the old sailing boats. The new capital Douglas with its ferry port flourished, hospitals and a sewage system were built and along the promenade posh hotel buildings were erected.

And then another new feature was added to Mannin’s attractions, which has remained one of the main magnets for tourists from all over the world to this day: in 1907, the first TT motorcycle race, one of the most spectacular and dangerous in the world, was held with 25 contestants – today, the spectacle brings thousands to the island every year!

The 20th century had its ups and downs for the Isle of Man: during both World Wars, alien civilians were interned on the island; after WWI there was immense poverty, unrest and a general strike led by Alf Teare which led to a housing programme for the poor; during WWII, the famous Manx Regiment fought in Crete and in North Africa with the Desert Rats.

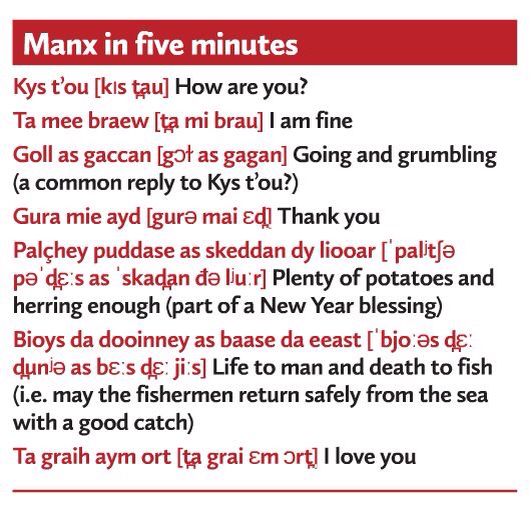

After WW II, politics took a rather conservative turn, and in 1961 the cutting of income taxes made the Isle of Man a popular destination for tax dodgers and offshore companies from all over the world. Also, though, people started caring about their language again – after an initiative from Irish Taoiseach Éamon de Valera, who sent the Irish Folklore Commission over to record native speakers talking in order to revive Manx before it’s too late: only 0.6% of the population were still speaking it in 1951! But fortunately, by 1974 when Ned Maddrell, the last native Manx speaker, died, the revival movement had already got going and young Manx people were learning the old language from the recorded audio documents.

Another field that became important to the Isle of Man is pop music: in 1964, the famous pirate station Radio Caroline North started broadcasting from its boat off Ramsey – supplying the youth of the whole of Northern England with modern music while all you could get on the BBC in those days was Mantovani and Frank Sinatra… And, of course, in the late 60s in faraway Australia, a pop band of three brothers emerged who would become Mannin’s most worldwide famous sons: the Bee Gees, Barry, Robin and Maurice Gibb! They had their heyday in the 1970s, writing and performing disco hits like “Stayin’ Alive”, “Night Fever” and “More Than a Woman”; there’s a statue of them on the Promenade in Douglas, just like the Beatles statue in Liverpool.

What they also did, though, was a most heartfelt version of the unofficial national anthem of the Isle of Man, “Ellan Vannin” – a beautiful declaration of love to the green fields and the sea surrounding the mythical old island…

Today, the Isle of Man is a mix of touristy areas, farmland, fishing villages, modern technology and an old-fashioned, laid-back lifestyle; much emphasis is put on the conservation of the Manx culture and language, and of the nature reserves: the whole island has been declared a UNESCO biosphere! Mannin, though a popular tourist destination, has kept its very own unique Norse-Gaelic character, and hopefully will continue to do so in the future.