My darling Ian and me had a very exciting and meaningful trip last week, dear friends: we visited the National Eisteddfod of Wales for the first time! Having lived in Wales for almost 5 years now, we knew about the importance of this festival, of course; though first time I’d heard of it was years ago, back at school in Germany, where we were taught about how it helps preserve the Welsh language and culture – its fame is international! And yet, neither Ian nor me had ever been to one, until last Friday. First of all, though, maybe I should explain for those who don’t know…

What is an Eisteddfod?

It’s literally a ‘sitting’ (from Welsh, eistedd – to sit), an indoors and outdoors event held entirely in Welsh, and it is the biggest culture festival in the whole of Europe. (We can vouch for that, we must have walked miles and miles exploring the whole ‘maes’!) In the course of a week, all sorts of competitions are held, singing, dancing, reciting, and most of all poetry – the tradition harks back to the days of the great Welsh bards of the 6th century, Aneurin and Taliesin.

Both children and grown-ups compete, alone and in groups; applying successfully and taking part is considered a great honour, and can even help you in your talents getting discovered!

The most prestigious prize, as mentioned before, is the poetry prize; in an elaborate ceremony, the winner is announced by the Archdruid and, accompanied by trumpets and druids, placed on the coveted bard’s throne, ‘Y Gadair’, The Chair. This year’s winner was Tudur Hallam, and the present Archdruid is Mererid Hopwood.

As I’ve said, the Eisteddfod has got a very long tradition, and it survived centuries of oppression of the Welsh people and their language; it has certainly played a part in upholding the people’s resistance and resilience, finally leading to the encouraging fact that the number of Welsh speakers increases every year (even including immigrants like me), and that all schools in Wales now teach in Welsh. So, how did this glorious festival develop?

The history of the Eisteddfod

As mentioned before, the legendary history of the Eisteddfod goes right back to the 6th century, the time when the Anglo-Saxons were expanding their kingdoms at the expense of the Celtic natives; most of them had been pushed West to what is now Wales, where they could preserve their culture and their language. Several little kingdoms emerged, the biggest one of them being Gwynedd, and king Maelgwyn Gwynedd (a descendant perhaps of king Arthur, but certainly of Cunedda, the founder of Wales) one day decided to hold a competition for the bards and minstrels of the country.

The tradition must have carried on at court through the centuries, but the first documented Eisteddfod was held in 1176 at Aberteifi (Cardigan) by Rhys ap Gryffydd, where two valuable armchairs were awarded, one for poetry, the other for singing – a tradition continuing until this day!

The Eisteddfodau continued, despite the wars with, and eventual occupation by, the English; in 1450, a three-month-long one was held at Caerfyrddin (Camarthen)! Life for the bards became more difficult, though, under the Tudors of all dynasties, even though they happened to be of Welsh origins themselves… While Henry VIII just chartered the Eisteddfodau, his daughter Elizabeth (even though she patronised two Eisteddfodau herself) had all Welsh bards examined and licensed and put under strict supervision – not least because of her suspicions that they might be involved in Catholic activities.

After her death and the beginning of the Stuart dynasty, Welsh nobles became more and more anglicised and didn’t put much emphasis on hosting Welsh-speaking festivals; the Eisteddfod at Glamorgan in 1620 only had an audience of four… In 1701, a campaign was started for the renewal of the tradition, advertised in cheap almanacs for the ordinary people to see, but that didn’t really catch on, either.

In 1788, though, the Gwyneddigion Society in London set up new rules for an annual National Eisteddfod – the rules that are still valid today. The revival started the following year in Corwen, and Gwallter Mechain won the competition – although it turned out later that he’d been informed in advance of the subjects for the poems…

At that time, the proceedings were still rather ordinary, conducted in hotels by ordinarily dressed people; but that would change soon thanks to Iolo Morganwg (bardic name of Edward Williams), who in 1792 founded the secret society ‘Gorsedd Beirdd Ynys Prydain’ (now known as Gorsedd Cymru) which invented new rituals for the Eisteddfod (implemented for the first time at Caerfyrddin in 1819) based on pre-Christian Druidry, which at the time was having a big revival all over Britain. We owe to him all the wonderful procedures we see today during the poetry competition and the award ceremony, from trumpets and elves to druids clad in ancient costumes!

The Eisteddfodau, now held in big open spaces, became bigger and more popular every year, patronised even by the English gentry (a teenage Princess Victoria visited in 1832). At the same time, though, social unrest spread through Industrial Revolutionary Britain and particularly Wales, where the working-class people and their language were systematically supressed. Insult was added to injury with the 1847 ‘Blue Books’ report on the ostensibly bad education in Wales – written by people who didn’t even speak Welsh! Sadly, this led to Eisteddfod poetry turning rather submissive and pro-England for a while.

In 1858, though, the Eisteddfod at Llangollen saw a number of outstanding poems on history, and a love poem by John Ceiriog Hughes called ‘Myfanwy’ which became an instant hit – and led to dismissive comments of the English press about the Welsh being so ‘sentimental’ about their ancient language. This, of course, encouraged the bards even more, and they founded Yr Eisteddfod, a national body that would from now on organise an annual National Eisteddfod in a different place every year, one year in the South and one in the North.

The poets of the late 19th century Eisteddfodau were elaborately praised and very highly regarded in society; in 1902, Thomas Gwynn Jones won the Chair for his poem ‘Ymadawiad Arthur’ (The Passing of Arthur), which gave the Arthurian legend back to the Welsh where it originally belonged. You can listen to the musical version of this hugely influential work on YouTube!

The Eisteddfod didn’t stop during the wars, either – but in 1917, the winner of the Chair, Ellis Humphrey Evans, didn’t answer the call at the ceremony because he had fallen in France a few days earlier. His Chair was covered in a black sheet, which is why the 1917 Eisteddfod is known as ‘Eisteddfod y Gadair Ddu’ (Eisteddfod of the Black Chair).

Politics began to play a role at the Eisteddfod: the celebration of Welsh culture, history and language at Pwllheli in 1925 inspired Saunders Lewis, Huw Robert Jones and Lewis Valentine to found a nationalist and social democratic party then and there – the birthplace of Plaid Cymru, which has been fighting ever since for an independent Wales!

Still, the number of Welsh speakers was declining, which prompted Saunders Lewis to his famous 1962 radio speech ‘Tynged yr Iaith’ (The Fate of the Language) and the foundation of Cymdeithas yr Iaith Gymraeg (Welsh Language Society), which started promoting the Welsh language like never before – and the Eisteddfod became one of the most important tools for that goal!

Today, as mentioned before, the annual National Eisteddfod is the biggest culture festival in Europe; the one we attended last week saw over 150,000 visitors and 6,000 competitors! We wandered all around the huge maes (field),

enjoyed refreshments and live music (our three little Celts, Ben, Lep and Nessie were with us as always, of course – Bennie wouldn’t have missed this event with anything!),

visited the various stalls from political parties, culture societies, bookshops and souvenir sellers,

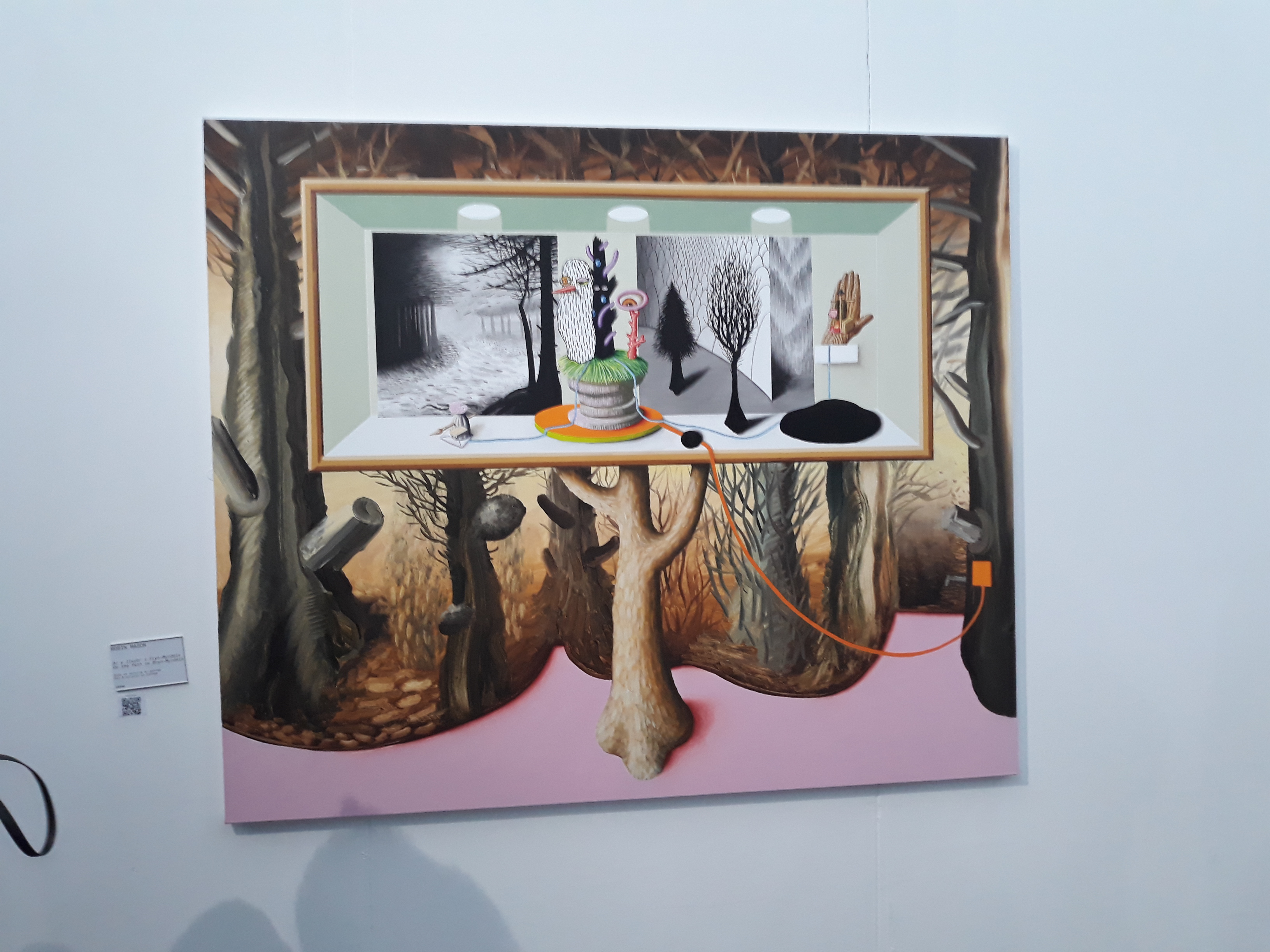

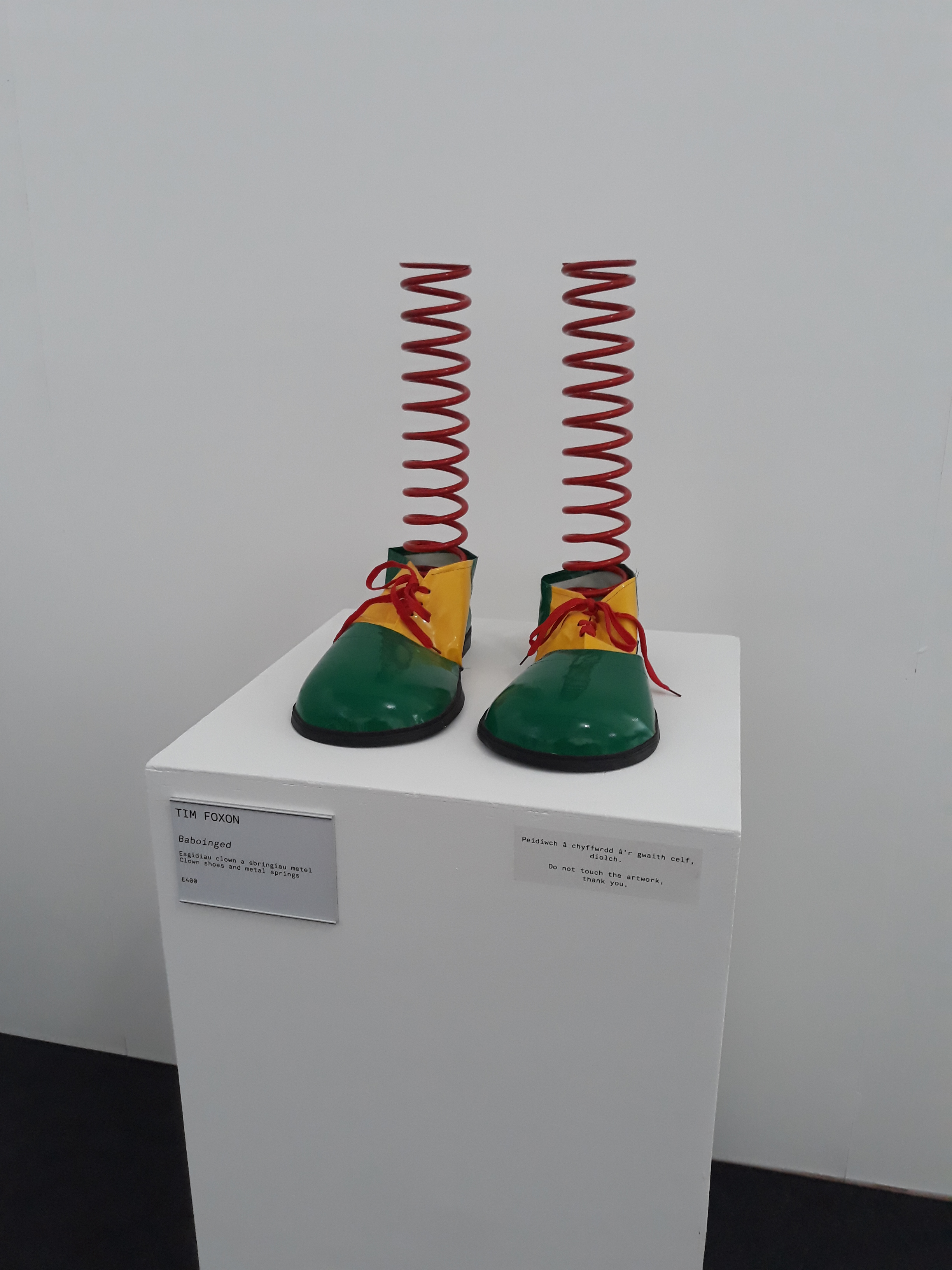

had a look into the tents where the competitions took place, and also the arts exhibition with very interesting works from contemporary Welsh artists.

And back home, of course, we unpacked our souvenirs: a celebratory plate, a set of coasters with stirring slogans for everybody who dreams of a free, independent, socialist Republic of Wales – and some books for me to practice my Welsh!

Whether you’re Welsh or not, whether you speak Welsh or not, dear friends – if you’re ever in Wales when the National Eisteddfod is on (which is usually in early August), drop in and feel the atmosphere, it’s just absolutely magical!